No products in the cart.

Origin and history of Mapacho

It is estimated that this plant is native to the Andean area, near Lake Titicaca and its cultivation dates back to between 5,000 and 3,000 years BC. between Peru and Ecuador. In Cuba, the acclimatization of the Nicotiana tabacum plant took place by the Aravaca Indians 2,000 years before Christ.

Among the peoples who used the Mapacho, are the Jíbaros of the Amazon, the Aruacos of the Orinoco basin and further north, the Aztecs. It was with the Arhuacos that he arrived on the island of Cuba, where he acclimatized about 2000 years BC.

However, the origin of this plant is much more remote, and is estimated to be eighteen thousand years old; A long time before it was cultivated, since time immemorial, the Mapacho was already smoked, snuffed through the nose in the form of snuff, chewed, eaten, drunk, and even used as drops in the eyes.

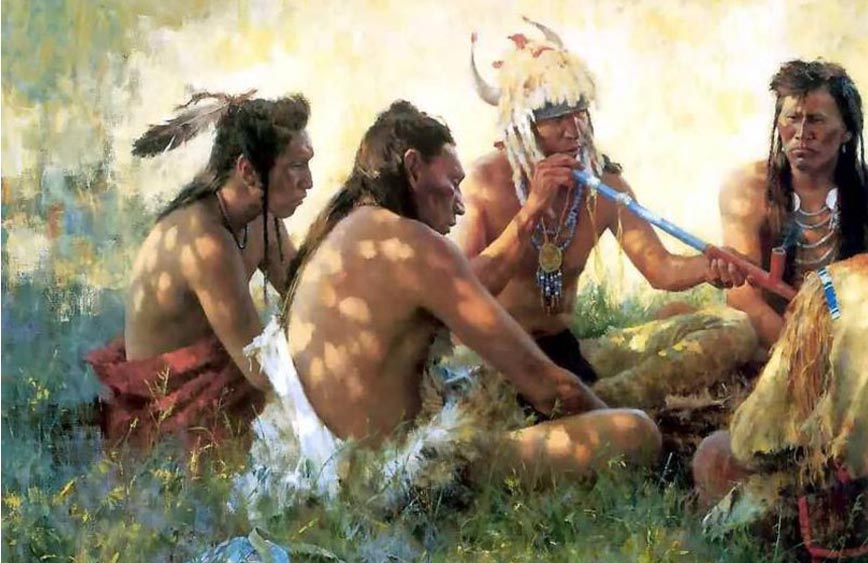

It was essential in religious ceremonies, and in all types of rituals: it was blown on the faces of warriors before fighting, it was spread in fields before sowing, it was offered to the gods, it was poured on women before sexual intercourse. , and both men and women used it as a narcotic; Throughout South America it was considered a miraculous medicine.

“When Native Americans introduced tobacco to European immigrants, they deliberately left out sage and other crucial consciousness-altering ingredients. On the one hand, they did so because of the spiritual principle of not releasing consciousness-altering substances to the spiritually unawakened. The Native Americans quickly saw that, although the Europeans had overcome poverty and were technically adults, they suffered from a curious and rather tragic spiritual retardation.

Europeans had no visions, could not communicate with the spirits of their ancestors, and did not feel the divinity of the four elements. Not only did they lack these perceptual abilities, which some Native Americans occasionally lacked, but they also arrogantly ridiculed those who could perceive such things. Clearly the Europeans were not ready for the rituals in which these plants were smoked […]

An additional reason why the Native Americans gave the Europeans the Mapacho without the other plants and the knowledge of how to use it, was a kind of biochemical warfare strategy, hoping to weaken these powerful enemies, and keep them away or not favor their access to other dimensions in which a state of clarity is achieved with which to solve problems.

Many have pointed out how Europeans induced Native Americans to become addicted to alcohol, but few have highlighted the more subtle but more powerful way in which Native Americans addicted their captors. Addiction and slavery are twin events in history, and one is hardly found without the other. The exchange of vices between oppressors and oppressed is a constant.”

Mapacho and the Mayans

Historians identify the use of the Mapacho plant in the Mayan culture in Chiapas, Campeche and Yucatán, where they found archaeological remains that document the ritual use of tobacco.

Quáuhyetl, that’s what the Mayans called the Mapacho. The ritual of sik’ar—which means smoking—gave its name to the “cigar.”

By analyzing the chemical residues present in a Mayan container more than 1,300 years old, scientists from the Center for Biotechnology and Interdisciplinary Studies (CCIE) at Rensselaer Polytechnic (USA) have shown that members of this pre-Columbian civilization already consumed Mapacho. (Published in the journal Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry).

The vessel is about 6.5 centimeters in diameter and shows Mayan hieroglyphs on the outside with the meaning “the house of its tobacco.” The vessel, which is part of the Kislak Collection at the United States Library of Congress, was made around the year 700 AD in the Cuenca del Mirador region, in southern Campeche, Mexico, during the Mayan period. classic.

Describing its ceremonies, several contemporary observers attribute narcotic and hallucinogenic effects to the Mapacho. This plant is widely consumed around the world without these effects being described, but entheogenic effects are described in some regions. This difference can be attributed to several combined factors: (1) the ancient Mayans could have used a variety of Mapacho with a higher concentration of active ingredients. (2) they smoked Mapacho at specific times but at high doses. (3) Other tools that induce altered states of consciousness were combined in the ceremonies, such as reverberation, songs, dances and different forms of music. On some occasions, they consumed herbs with hallucinogenic properties simultaneously with the Mapacho or instead of it.

In the book Popol Wuj, which recounts the originsenes of humanity, the actions of the gods and the history of human beings until 1550, there is evidence of the importance of the Mapacho in the Mayan culture. In one episode, the twin gods are subjected to a test in which they must spend the night in a cave, in total darkness, and keep their cigarettes lit. Instead, the gods put out their cigars, but put fireflies on the tips of the cigars with the intention of deceiving the Lords of Xibalba, making them believe that the cigars remained lit. The next morning, the gods lit their cigars again and left the cave victorious.

The objects that the Mayans apparently used for smoking can be divided by size between cigars and cigarettes. In some cases the cigarettes are painted white, giving the impression that the Mayans either wrapped their Mapacho in another substance, such as tusa, very similar to the way cigarettes are wrapped today, or applied some coating, such as cal, to the Mapacho.

Mapacho and the Aztecs

Several specialists point out that, during their journey to the north of the region, the Mayans transmitted the use of the Mapacho to the Toltecs, who inherited this culture from the Aztecs.

Dominated by rigid laws and curtailed by numerous taboos, the civilization of the Aztecs or Mexicas nevertheless knew how to develop effective medicine and pharmacopeia. Despite this, Aztec therapeutic practice was a mixture of magic, knowledge verified by experience and religion.

The Aztec sculpture of Xochipilli, where the tobacco flower stands out (Canudas, 2005).

The Aztecs showed reverence for the Mapacho, as they did for cacao and pulque; Even for Mapacho products there was a traditional norm on the specific and exclusive conditions of their use among the ruling class, priests and warriors; as well as, to severely punish any other member of the population who failed to comply with that rule (Pascual and Vicéns, 2004). For his part, Canudas (2005) also mentions the appreciation of the Aztec gods towards the multifaceted properties of tobacco.

History of the Mapacho in Europe

In Europe, the Mapacho was described for the first time by the first chroniclers of the Indies. Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdez, in his work Historia General de las Indias (Seville, 1535), writes: «Among other reprehensible customs the Indians have one that is especially harmful and that consists of absorbing a certain kind of smoke through which they call “tobacco” to produce a state of stupor.

For Europeans, the Mapacho was discovered by two Spanish sailors who, carrying out orders from Columbus, were exploring the interior of the island of Cuba, a month after the Pinta, the Niña and the Santa María made landfall. The beaches of San Salvador were the scene of the discovery; When the two sailors reached the shore, the natives welcomed them with fruits, wooden javelins, and certain “dry leaves that gave off a peculiar fragrance.”

Rodrigo de Jerez and Luis de la Torre, companions of Christopher Columbus, were the first Westerners to know of its existence. Rodrigo, upon his return to Spain, was imprisoned by the Inquisition accused of witchcraft, since only the devil could give a man the power to draw smoke from his mouth.

Columbus was surprised by the use of the Mapacho in religious and social ceremonies, since for the Indians tobacco had magical powers and pleased the gods. Mapacho was considered a panacea: it was used to combat asthma, fevers and convulsions, intestinal and nervous disorders and even animal bites.

By order of Philip II, Hernández de Boncalo, chronicler and historian of the Indies, was the one who brought the first Mapacho seeds that arrived in Europe in 1559. These seeds were planted in lands located around Toledo, in an area called Los Cigarrales, because they used to be invaded by pests of cicadas. The cultivation of tobacco in Europe began there and, for this reason, some historians maintain that the name cigar comes from this circumstance.

After a few years, around 1560, the Mapacho was already known in Spain and Portugal. The French ambassador to Portugal, Jean Nicot de Villemain (1530 – 1600 AD), aware of the multiple medicinal properties of the Mapacho, sent it to his queen, Catherine de Medici, as snuff powder, to relieve her migraines (Charlton, 2004 ; Pascual and Vicéns, 2004), and hence the Mapacho was called “queen’s herb”, “nicotiana” or “ambassador’s herb”.

Catherine de’ Medici suffered from severe headaches and listened to the ambassador when he recommended that she take the plant in the form of snuff. The pain disappeared and raccoon began to be used as a medicine in France and the rest of Europe. When Linnaeus published his Species Plantorum, he chose the scientific name Nicotiana tabacum in homage to Nicot.

The etymology of the word Mapacho is controversial. One version proposes that “tobacco” comes from the place where the plant was discovered, either Tobago, an Antillean island, or the Mexican town of Tabasco. The most coherent version is that it comes from the Arabic “tabbaq”, a name that was applied in Europe since at least the 15th century to various medicinal plants.

In 1584, Walter Raleigh founded the colony of Virginia in North America, copied the custom of pipe smoking from the indigenous people, and began cultivating the famous Mapacho from that territory, which was introduced to England in the time of Elizabeth I. A few years Later, the Mapacho had become the main economic resource of the English colonies. The great maritime voyages of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries around the world helped bring the Mapacho and the habit of smoking it to the coasts of Asia, Africa and Oceania.

In Japan, Russia, China and Turkey, the use of Mapacho was initially combated with drastic measures, to the point that Sultan Murad IV ordered the execution of numerous smokers and, in 1638, the Chinese authorities threatened to behead the Mapacho traffickers. . Over time, the Turks joined the global tobacco market and became heavy smokers, just like the Chinese.