Rapé from the Nukini tribe:

Nukini Tribe

The Nukini are an Indigenous people of the Amazon, belonging to the Panoan language family. They live in the Juruá Valley region of Acre State, Brazil. They share a similar way of life and worldview. Throughout history, they have suffered expropriation, exploitation, violence, and the plundering of their habitat’s resources by rubber companies in the mid-19th century.

Today, after a long struggle that united all the Amazonian Indigenous peoples of Brazil in the mid-1970s, the Nukini Indigenous Territory is part of Brazil’s protected areas. It is located near Serra do Divisor National Park, part of whose territory the Nukini claim as their own.

One of the main challenges for this community is ensuring its physical and cultural survival, as well as the protection of the rainforest, which is constantly threatened by loggers, hunters, and traffickers.

Nukini Language

The peoples who share the Panoan ethno-linguistic family, located in the western Amazon, have great territorial, linguistic, and cultural similarities, but we must not forget their internal diversity.

The Panoan language belongs to the Pano-Tucanoan language family, which includes several languages spoken by Indigenous communities in the Amazon basin, primarily in Brazil, Peru, and Bolivia.

Regarding their name, the Nukini had other self-designations in the past. For example, we see how some historical texts also refer to the Nukini by the terms Inucuini, Nucuiny, Nukuini, Nucuini, Inocú-inins, and Remo.

Currently, few Nukini still speak their native language. Unfortunately, the rubber tappers ridiculed and discriminated against them for speaking their language, so they stopped passing it on to their descendants, opting instead to educate new members of the clan in Portuguese.

Nukini History

Throughout the 19th century, the Nukini, then known as the Remo, were located east of the Ucayali River, near the Canchahuaya hills.

At the beginning of the 20th century, there are mentions of the Remo in the upper Juruá Mirim region, on the upper Tapiche River.

In Peru, they were used as payment for a rubber tapper’s debt. Without delay, the Nukini fled Peru and returned to their village in the Gibraltar rubber plantation, located in Brazil.

This was a time of great conflict for the Nukini. Their “friendship” with the rubber tappers, for whom they were nothing more than a source of labor in a dangerous and unfamiliar territory, was a source of conflict. The rubber tappers’ attempts to “civilize” the Nukini, who did not fully accept Brazilian or Peruvian culture (depending on which side of the border they were on), were also a source of conflict. It was an extractive culture centered on economic values.

Even until the mid-20th century, the Nukini continued to be located in the Môa River region, as can be read in the accounts of various travelers. Oppenheim, for example, refers to them as being located on the border with Peru, in the basin of a tributary of the upper Moa River:

The Nukini survived epidemic fevers and also the expansion of rubber exploitation. During the first decades of the 20th century, they were incorporated into the rubber industry and remained in the Môa River region to this day. For decades they worked with the rubber barons, only receiving official recognition of their lands in the late 1970s, and they remained in this area even after rubber extraction had ended.

It was in 1977 that the demarcation of the Nukini Indigenous Territory officially began. On that occasion, based on a report by anthropologist Delvair Montagner, its area was estimated at 23,000 hectares.

Subsequently, in 1984, a group coordinated by anthropologist José Carlos Levinho was appointed to conduct a study of the territory with the aim of defining the “Indigenous Area.” In their report, they presented a proposed area of approximately 30,900 hectares for the Nukini Indigenous Land.

Since then, their territory has been demarcated and protected. However, starting in 2000, the Nukini began to question the northern and western boundaries of their land, claiming a portion of the Serra do Divisor National Park.

The Nukini and the Remo

Could the “Nucuinis” of the Paraná de la República and Alto Igarapé Ramon be from the same tribe as the indigenous people settled along the banks of the Jaquirana River? Or is this another tribe encountered by early explorers, called the “Rhemus,” now extinct or absorbed by the present-day “Nucuinis”?

Braulino de Carvalho, of the Boundary Commission, found some families of Remo Indians on the right bank of the Jaquirana River who called themselves “Nucuinis,” leading anthropologists to believe that this is the same tribe, the Nukini tribe, which has adopted different names throughout history, either as a self-designation or because this was the nickname given to them for a time by rubber tappers.

Moa River

Nukini Geography

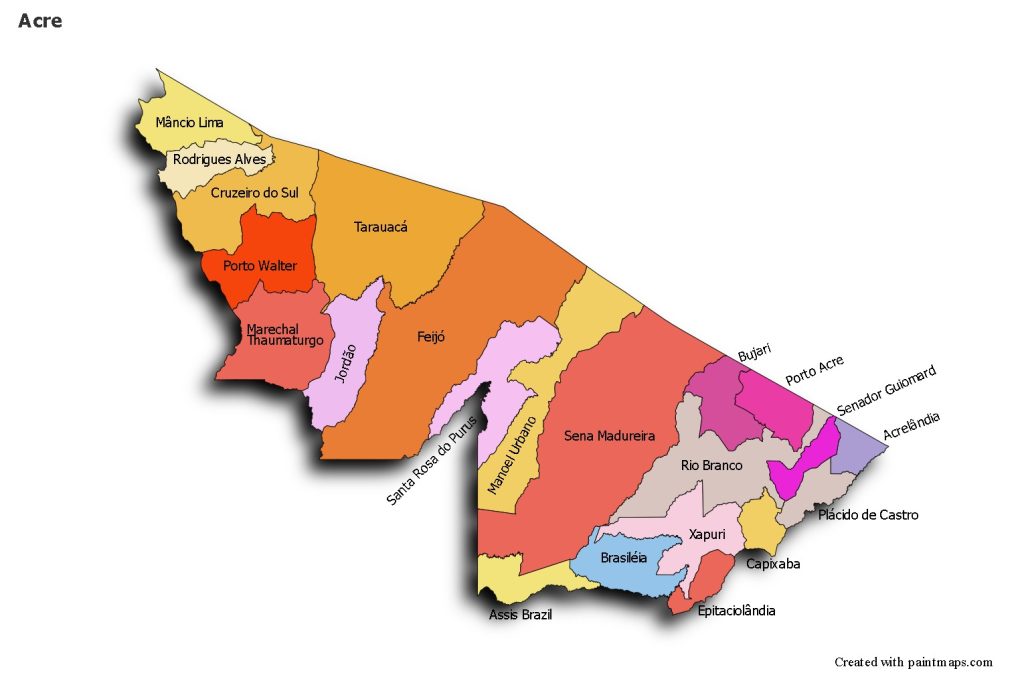

The Nukini Indigenous Territory is located in Acre, in the southwesternmost part of the Brazilian Amazon, and forms part of one of Brazil’s most important mosaics of protected areas.

Most Nukini families are distributed along the Timbaúba, Meia Dúzia, República, and Capanawa streams, and on the left bank of the Môa River.

The state shares international borders with Peru and Bolivia, and national borders with the states of Amazonas and Rondônia. In the westernmost part of the state lies its highest point, where the landscape is altered by the presence of the Serra do Divisor, a branch of the Peruvian Serra da Contamana, with a maximum altitude of 600 meters.

The biodiversity value of the Serra do Divisor National Park (PNSD) is among the highest found to date in the Brazilian Amazon. This biological diversity has been used and conserved for centuries by the area’s resident population, including the Nukini, whose lands harbor a large portion of the biodiversity.

The soils of Acre support natural vegetation composed of dense tropical forest and open tropical forest, characterized by their floristic heterogeneity. The climate is hot and humid equatorial, marked by high temperatures, high levels of precipitation, and high relative humidity. Acre’s hydrography is formed by the Juruá and Purus basins, right-bank tributaries of the Solimões River.

The Juruá River basin covers approximately 250,000 km². The total length of the Juruá River is 3,280 km, with a drop of 410 meters. It originates in Peru at an altitude of 453 meters under the name Paxiúba, later joining the Salambô River. From then on, it is called the Juruá River, which flows through the northwestern part of the state of Acre do Sul toward the north, and later enters the state of Amazonas, finally emptying into the Solimões River.

This Amazonian area has an environmental diversity considered among the most important in the Brazilian Amazon, making it crucial that Indigenous peoples, for whom environmental conservation is a fundamental principle, defend their lands against loggers, ranchers, and extractive industries driven by economic and commercial priorities.

Nukini Cosmovision and Shamanism

The Nukini are a highly spiritual people. Like all Amazonian peoples, they have a shaman or “pajé” in charge of the spiritual affairs of their small society. The “pajé” is responsible for preparing and distributing medicines to their people.

As Erison Nukini, one of the spiritual leaders of the Recanto Verde village in the state of Acre, Brazil, tells us: “Snuff, body paint, songs, and uni (ayahuasca) are essential parts of my spiritual vision.” This worldview is being reconstructed after having disappeared due to the imposition of the rubber barons.

Ayahuasca (which they call “uni”) is another of their main medicines, used in rituals attended by all members of the tribe and, if present, visitors to the village. Thanks to this brew, the Nukini, like other Amazonian tribes, are able to connect with the rainforest, the spirits, the rivers, the trees, and the mountains. In this way, they are able to live in harmony, preserving the forest to ensure the continuity of life for future generations.

Paulo Nukini, chief of the Jaguar people, who has held this leadership position for 20 years, tells us that his grandfather gave him this knowledge when he was a child, sharing with him different experiences, customs, and traditions. He also taught him how to listen to the rainforest and how to lead his people to harmony among themselves and with the land they inhabit.

They also produce beautiful ceramic crafts, including plates, cups, and vases. They use the ash from the shells of the carpio tree to mix with the clay. With other materials, they make brooms, baskets, and other items.

The seeds of the urucum tree, for example, are used to paint their bodies. First, they are crushed with water, and then a paste is formed, which they use to adorn their bodies and which also serves as a food coloring. The cipó-titica (Heteropsis flexuosa) is used to make baskets and various ornaments, which are painted with urucum and genipa americana.

Mariri

Regarding rituals, the Nukini currently dance the mariri – as do several Pano peoples in the region – and sing numerous indigenous songs, some composed by them and others learned from elders.

Nukini Life

Due to intense contact with rubber tappers, the Nukini adopted many of the customs of the small-scale farmers and river dwellers who inhabit the upper Juruá region. For example, they adopted the Portuguese language. Despite this, they continue to maintain their own social organization.

The Nukini are organized by clans. The elders are able to precisely define the entire patrilineal lineage of Nukini families, classifying their members according to the clan to which they belong: Inubakëvu (“people of the jaguar”), Panabakëvu (“people of the açaí”), Itsãbakëvu (“people of the duck”), or Shãnumbakëvu (“people of the snake”). However, many young people in the Nukini community do not know which clan they belong to, so they disregard it as a criterion when choosing a partner to start a family.

Their houses are generally built with resources from the rainforest and are called malocas. Some houses have walls and floors made of paxiubão (tree) and roofs covered with palm leaves, especially from the Caranaí palm. Other dwellings are built with walls and floors of planks, generally using good quality wood (yellow bark, bacurí, copaíba, red cedar, louro). The pillars and beams are constructed with maçaranduba, muirapiranga, abacate, and yellow lapacho. There are also houses with aluminum roofs, primarily used in schools and health centers. These are generally donations from government agencies or NGOs.

Descent is patrilineal, as is the case in most Pano communities. Work is divided by age and gender. Men are responsible for hunting, gathering, and agriculture. Women are involved in domestic life, crafts, and, to a lesser extent than men, gathering forest products and farming.

Politically, the Nukini currently have a system of representation based on elections. They elect the community’s political leader, the president of the agricultural association, and the community’s representative to the Advisory Council of the Sierra del Divisor National Park, established in 2002.

Activities

The Nukini do not have a developed collective economy; rather, production is usually family-based. However, there are some activities they carry out collectively:

Fishing, which occurs mainly during the dry season, is done with nets and hooks. Small fish like piaba are used as bait. The Nukini typically fish in small lakes in the area (Timbauba, Montevidéu, Capanawa, etc.) rather than in rivers. This is a secondary source of food, as fish are not very abundant in the area inhabited by the Nukini, so they supplement it with hunting and agriculture.

The current problems facing their people are primarily the proliferation of settlements bordering their protected Indigenous Territory. On the one hand, these settlements are inhabited by hunters who hunt to sell food or exotic animals. This causes animals to move away from these territories, making hunting a difficult activity for the Nukini, so they must raise and herd a larger number of animals. Furthermore, other settlements near their lands are searching for oil in the area, which appears to be rich in this energy source, leading to the destruction of the ecosystem that is sacred to their people.

Regarding hunting, the wild animals that form part of the Nukini diet include the paca, the agouti, deer, paca, turtles, coati, leatherback armadillo, flat-tailed armadillo, tapir, jacu, mutum (a type of bird), and monkey. They use different hunting techniques: traps, dogs, or what they call “hunting on the move” and “hunting from a blind.” For hunting on the move, hunters venture deep into the jungle on foot for four hours, leaving their families behind until they find their prey. Hunting from ambush, however, can take place near plantations, which are usually located close to the huts.

In addition, the Nukini raise some animals for their own consumption, such as pigs, chickens, and sometimes sheep, goats, and cows. In the hunting areas, the Nukini also gather various foods: lacaba, pauta, buritu, and palmito are some of the fruits they eat.

They also find medicinal plants in the forest that they use daily, such as palo-amargo (used for insect bites), and different tree barks that serve as tea, such as the bark of the carob tree, the copaiba tree, or the cat spider, which also has relaxing and anti-inflammatory properties. They use quinine tea against malaria. They also use the sap of the cipó-guaribinha tree to combat the flu and its various forms. Plants like marshmallow are used for coughs, and watercress for toothaches. In addition to what they find in the rainforest, the Nukini cultivate a variety of plants. Among the fruits they grow are mango, coconut, cashew, jackfruit, pineapple, lemon, acerola, guava, avocado, palm heart, cupuaçu, and papaya, among others. Their plantations primarily cultivate corn, rice, cassava, beans, sugarcane, tobacco, and yam. Any surplus production is sold to obtain other products that are unavailable in their territory. Cassava flour is their most widely sold product.