Rapé from the Huni Kuin (Kaxinawá) tribe:

Huni Kuin

Huni Kuin

Huni Kuin

Huni Kuin

Huni Kuin Tribe

The Huni Kuin tribe lives in small communities located from the foothills of the Peruvian Andes to the Brazilian border, in the states of Acre and southern Amazonas, encompassing the Alto Juruá, Purus, and Javari Valley.

Territory

Their native language is Hatxa Kuin, “the language of truth,” from which their name derives: Huni, meaning “man,” and “kuin,” meaning “true.” The Huni Kuin refer to themselves as “true man.” Today, almost all are bilingual (speaking Spanish or Portuguese, depending on the area) in order to communicate and sometimes trade with the outside world, although within their communities they speak only their native language.

This tribe is divided into small communities or villages that remained isolated in the virgin rainforest until 1946, far from the rivers navigated by merchants. Some of these communities still have virtually no contact with the Western world. In recent decades, they have undergone a significant transformation, both in terms of internal migration (many Peruvians have moved to the Brazilian side) and in their way of life.

The Huni Kuin are also called Kaxinawá, perhaps because of their ability to move at night through the dense jungle, since “kaxi” means “bat” in Huni Kuin.

Huni Kuin Life

The ecosystem in which the Huni Kuin (or Kaxinawá) live is divided into three distinct areas:

First, there is the village, made up of family homes, open-sided dwellings without walls, and malokas, communal spaces that are also roofed and open. All the buildings are constructed entirely from materials found in the rainforest. They generally sleep in hammocks, although they do have some mattresses.

Next to the houses are the chacras, the cultivated fields. Then there is an area of the rainforest with a significant human presence and open paths. Finally, there is the deep rainforest, the largest virgin rainforest in the world, which is so difficult to penetrate.

They grow some vegetables and fruits: mainly cassava, corn, beans, plantains (in all their varieties), peanuts, watermelon, papaya, pineapple, and açaí. They make a flour from cassava that they use in practically all their meals. They also make some fresh fruit juices, such as açaí juice.

They buy some food, so they sometimes accompany their meals with rice or pasta, although it’s not the norm. Their food is supplemented with whatever they manage to hunt, whether meat or fish. This community eats all kinds of meat except for their sacred animals: snakes, eagles, and the urbú (a member of the condor family). They eat all other animals. The men are the hunters, but not all of them.

A small group of them has the role of hunter, a role bestowed upon them by their ancestors as well as by their more athletic physiques, since they sometimes walk all day, for many hours, in the jungle. They have to know the jungle and its animals very well. They know them even without seeing them; they can feel them, hear them, and smell them.

The hunters also have a profound sense of jungle ethics. They don’t kill anything they won’t eat, and they try to remain as inconspicuous as possible. It is normal for two men to go hunting, no more, to minimize their impact while still ensuring their safety. When they go fishing, however, men and women go together.

If a village migrates to other lands and abandons its settlement, it will be swallowed by the jungle and will disappear completely under its thick green mantle within a maximum of five years.

Huni Kuin Customs

The testimony of a European therapist who lived for two months in a small Huni Kuin community of about 50 people tells us: Everything is interdependent with the jungle. Absolutely everything. They are part of the jungle and act like nature itself.

This is a very traditional community; they have incorporated virtually nothing from the Western world into their lives. And to preserve this tradition in an authentic way, they rely primarily on the use of their language, their food, their history, their connection with the jungle, their spirituality, their music, their customs, their ancestral stories and knowledge, and their sacred medicines.

Their daily lives revolve around the survival of their community in the jungle. It’s that simple and that complex. Depending on the tasks, sometimes they separated into men and women, while other times they worked together.

The social life of the Huni Kuin is strongly defined by gender. The man is the predator, the hunter; he brings back meat and raw materials from the jungle. He is the nomad, the intrepid one who ventures into the depths of the rainforest.

The woman transforms what the man brings from the outside world and uses it for their own purposes. She is in charge of crafts, gathering plants, cooking, and raising children.

The man is responsible for building the house, and the woman for decorating and caring for it. The man prepares and plants the fields, and the woman is responsible for tending them and harvesting the food. The woman, in principle, never ventures into the virgin rainforest.

However, although their tasks are separate on the material and practical plane of life, both men and women are very much united on the spiritual level of all these tasks. It is a very dual organization, but neither part overlaps the other, neither is subjugated; both are part of the one, of the whole.

Habits of the Huni Kuin

We could describe a typical day in a small Huni Kuin village in the heart of the Amazon as follows: They get up before dawn, around 5 a.m. From 10 a.m. onward, it starts to get very hot, so they try to finish all the strenuous work before then.

Around 10 a.m., they eat something and rest. There is no standard schedule for the tasks that need to be done. Every morning, after breakfast (there is no difference between the food they eat at breakfast or dinner), the boss first meets with his family to talk about what needs to be done at that moment to organize the work for the day.

Afterward, he joins the rest of the community. This gathering occurs completely naturally, and everyone participates regardless of sex or age. No one is obligated to do any work; everyone is aware of what is necessary for their own survival as a tribe, and that is why they work all day.

There is no marriage ceremony among their rites. A couple’s union is consecrated when the young man prepares the field for his beloved. Although parents intervene in these unions for their own interests, they cannot force the young people to be together against the will of either of them. There are, however, many ceremonies that are performed methodically, such as fertility rites or those marking the transition from childhood to adulthood.

The Huni Kuin do not have a word to refer to humanity or human beings. They distinguish, on the one hand, the kuin (themselves) and, on the other, the bemakia (“the other, the others”). For them, the Huni bemakia include both the Incas and the white people.

There is an intermediate group between these two groups, the Huni Kayabi, indigenous people of the same linguistic group, Pano. So, to say “all of humanity,” the Huni Kuin would say “dasibi huni inun betsa betsapa,” which could be translated as “all of us and the others who are different.”

Huni Kuin Cosmovision

It is important to remember that for the Huni Kuin, all plants of the rainforest are sacred and medicinal. One of the most deeply rooted customs of this tribe is the plant bath, which they perform very frequently. For these baths, they choose a plant they need (they have an astonishing knowledge of the flora that surrounds them), boil it, and bathe with this aromatic water.

This bath has unimaginable therapeutic qualities, capable of restoring energy, relaxing muscle aches, reducing swelling in the body, aligning the chakras, and dispelling negative thoughts and worries. The recommendation of a shaman or pajé (the community’s herbalist) is not necessary for this bath.

This action, which may seem so simple, reveals the intrinsic wisdom of all members of a community regarding the nature to which they belong and immerses us in their cosmovision as beings who belong to the rainforest, with no distinction between it and the people who inhabit it.

The “Pajé”

The “pajé” has a connection with plants. They possess a comprehensive knowledge of all the plants that inhabit the rainforest, and they also have a spiritual connection with these plants and with all natural medicines. They are as important a figure as the shaman, although there is a slight difference between them.

The “pajé” therapist communicates with plants, and their role is to cure any type of illness or ailment through plants and natural medicine made from them. The shaman communicates with spirits, and that is their work. People go to them when they need something related to a spirit.

Shamans have knowledge that comes from past lives and also from their ancestors. They didn’t choose to be shamans; they are born shamans. Their role is to connect with the spirits. Shamans, as well as shamans, undergo long periods of initiation into various processes, following specific diets in which they abstain from meat, fish, salt, sugar, and sexual relations. This is how they appear pure before the spirits and can connect with them.

For the Western world, all this knowledge is truly difficult to grasp, but in this community, children are instructed from a young age in the knowledge of plants, animals, ancestors, the elements, Mother Earth, the astral plane, and spirituality. If you are connected to the here and now, you will receive all the instructions necessary to learn and grow.

The learning process of the herbalist (shaman) is quite different from that of the shaman. Unless dealing with poisonous plants, the herbalist is not subject to fasting and can carry out their normal activities of hunting and married life. They acquire their knowledge through apprenticeship with another specialist and require a keen memory and perception.

Despite the knowledge possessed by both the shaman and the healer, they do not become figures of authority. There is a freedom that transcends any individual; every person is free to do as they please, and all are subject to the implacable laws of the jungle, not of humankind. The “self” does not exist as something separate from the community or the jungle.

When someone transmits information, they do not do so from ego, just as the others do not listen from a place of subjugation. There is a profound awareness that the transmission of information has a purpose beyond the will of humankind. There is less thought, and that is because the “self” is not so important.

Everything is awareness and connection. Things are simpler because life there is inherently complex. Mother Earth has no borders; she is a single organism, and humans are part of her. We only need to listen to her to connect with her and, therefore, with ourselves.

In their worldview, the Huni Kuin imagine a hill that represents the world. At its summit lies the center, and from it spring all the rivers that stretch out until their opposite bank is hidden from view. At its base lives a tarantula, mistress of the cold and of death. The sky extends beneath the earth until it meets the horizon.

The Huni Kuin imagine themselves living atop the hill, while the “huni bemakia,” that is, the rest of humanity who do not belong to their tribe or linguistic community, live below. Currently, they are closer together, as the Huni Kuin have descended from the summit, and the white people have managed to cross the serpentine rivers with the help of a large crocodile.

The Huni Kuin maintain that the true shamans, the “mukaya,” those who carried within their bodies the shamanic substance they call “muka,” have died. But this does not prevent them from practicing other forms of shamanism, considered less powerful, but equally effective. Thus, they affirm at the same time that there are no shamans and that there are many.

A characteristic of Huni Kuin shamanism is the ability to heal or to cause illness. The invisibility and ambiguity of this power are linked to its transience. Shamanism is more of an event than a fixed role or institution within society. This is also due to the strict rules of abstinence required of a shaman: they cannot eat meat or have relations with women.

The use of ayahuasca is a collective practice among the Huni Kuin, experienced by all men and women, adults and adolescents, who wish to see “the world of ayahuasca.” The “mukaya,” the shaman, needs no substance, no external aid to communicate with the invisible side of reality.

The Yuxin

All adult men are, to some extent, shamans insofar as they learn to control their visions and interactions with the world of the “yuxin,” which we could translate as “the spirit world.”

This is due to the repetitive, frequent, and popular use of ayahuasca, which they consume two to three times a month, as well as the long, solitary walks that some elders take without a practical purpose, such as hunting or gathering medicinal herbs. These walks are rather intended to establish an active connection with the world of the “yuxin.”

Ayahuasca, called “nixi pae,” comes from a giant vine (marirí) and the chacruna tree; both plants have beautiful flowers. The mixture of these two plants in a specific preparation results in the ayahuasca brew. It’s common for these plants to grow around the village in these communities, so you don’t have to venture too far into the jungle to find them.

Preparation takes at least a full day (sometimes even longer), and they usually brew more medicine than needed for a single ceremony, so there’s enough left over. This way, the community has enough medicine prepared whenever it’s needed.

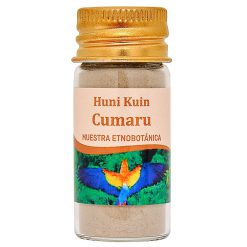

Another sacred medicine used in ceremonies is rapé, which is prepared with dried tobacco leaves (sometimes they grow their own, or buy from other communities in the area) and ashes from other jungle trees, all crushed into a very fine powder.

This mapacho powder is projected using a kuripé. The rapé is placed inside the kuripé, then one member of the community inserts one end of the kuripé into a nostril while another blows, projecting the substance that the first person inhales. There are many different varieties of rapé depending on the plants used to mix with the tobacco. Each one responds to a different spirit and purpose, but all the formulas share the goal of clarifying the mind and enabling sound decision-making, a property inherent to the tobacco plant itself.

Another very important medicine used by the Huni Kuin is “sananga.” It consists of extracts from the roots of a tree mixed with other liquids, usually lemon, and is used by placing a few drops in the eye. It deeply cleanses the eyes and improves vision, in addition to providing a strong, clean, and focused energy.

There are two types of sananga, one for women and one for men, although both are used interchangeably. The women’s sananga is much gentler, causing less burning in the eye. It helps promote tranquility and meditation, and has the ability to relax without losing focus.

It possesses feminine energy and wisdom. The men’s sananga, however, is very strong—one of the strongest medicines I have ever tried. It is used primarily before embarking on a journey, or before going hunting, or when someone needs a very strong cleansing, a purge.

In Huni Kuin ayahuasca ceremonies, it is very common to use “kambó” during the closing. This medicine consists of an extract of the venom of a specific Amazonian toad (kambó) that possesses incredible detoxifying properties.

It is capable of cleansing both the physical and etheric bodies; that is, it can break up a kidney stone and expel it from the body, as well as release accumulated anger that one carries within their personality, sometimes unconsciously, over the years. This medicine is essential for the Huni Kuin.

None of this is something that is simply “consumed.” These are medicines with which one must be very conscious because they are truly potent, and they can certainly help heal both physical and psychological illnesses, but they must be taken with the necessary intention and awareness. All these medicines have the ability to harmonize the mind, body, and spirit, balancing each of these forces.

Each medicine is always used ceremonially. And the ceremonies take place whenever necessary, and that need is discussed within the community, in harmony with the spirits and ancestors. The medicine always brings us information about what we are experiencing. The ceremonies can be family-based, or involve the entire community, or are held in conjunction with other communities… There is no specific context; there is simply a profound connection.

The medicines connect us with all that our eyes cannot see but that exists. They are a path to healing and transformation; their function is to harmonize the body, mind, and spirit.

They connect us with the mystery of life, our light, our soul, our heart, with Mother Nature, our ancestors, the astral plane… A specific frequency is needed to connect with this other world, and this is the purpose of sacred plants: to make you vibrate at the same frequency as the jungle, Mother Nature.

“Yunxidad” is a word that encapsulates the shamanic worldview of the Huni Kuin, a vision that does not consider the spiritual (yuxin) as something supernatural or superhuman, located outside of nature and outside of humanity, but rather understands the spiritual as the vital force (yuxin) that permeates all living things on Earth: people, the jungle, animals, waters, and skies.

In our daily lives, we see one side of reality, where this universal kinship of living things is not revealed: we see bodies and their immediate utility. In altered states of consciousness, such as after ingesting ayahuasca, human beings confront another side of reality, where the spirituality inhabiting certain plants or animals reveals itself as “yuxin.” Because it manifests both as a vital force and as a soul or spirit with its own will and personality, no single term adequately captures the ephemeral and multifaceted nature of the “yuxin.”

In the Purus region, the Huni Kuin themselves translate “yuxin” as “soul” when referring to the yuxin that appear at night or in the twilight of the jungle, in human form. The use of this word stems from their coexistence with the rubber tappers, who also see and speak of souls. When speaking of a person’s “yuda baka yuxin” or “bedu yuxin,” the term “spirit” is used more frequently.

The shaman’s activity, which attempts to connect and relate to the “yuxin,” is indispensable for the well-being of the community. The ultimate cause of all discomfort, illness, or crisis originates in this “yuxin” aspect of reality. The shaman’s role is to be the mediator between the two aspects. Places with the highest concentration of yuxin are ravines, lakes, and trees.

The Muka

The power of the yuxin, revealed in their capacity for transformation, is called muka. Muka is a shamanic quality sometimes embodied as a substance. A being with muka has the spiritual power to kill and heal without using physical force or poison (remedy: dau). A human being can receive muka from the yuxin, which opens the path for them to become a shaman, pajé, or mukaya. Mukaya means “person with muka” or, in the translation of Deshayes, “pris par l’amer” (“taken by the bitter one”).

The shaman plays an active role in the process of accumulating power and spiritual knowledge, but his initiation only occurs through the initiative of the yuxin. If the yuxin do not choose him, they do not take him; his solitary walks in the forest contribute little. Once taken by them, however, the apprentice becomes ill in the eyes of humans (“they become ill when a woman comes near them”). The yuxin’s weak point is the body, the man’s is his yuxin; “yuxinness” threatens the man’s body, and the body, the (feminine) blood, threatens the yuxin’s head.

If the man who has been taken wishes to follow the path of the mukaya, he submits to prolonged and severe diets (sama) and seeks another mukaya to instruct him.

Another characteristic of Kaxinawá shamanism (Huni Kuin), Expressed by the name mukaya, it is the opposition between bitter (muka) and sweet (bata). The Kaxinawá distinguish two types of remedy (dau): sweet remedies (dau bata) are forest leaves, certain animal secretions, and body ornaments; bitter remedies (dau muka) are the invisible powers of the spirits and of the mukaya.

The herbalist’s learning process is quite different from that of the shaman. Unless dealing with poisonous leaves, the herbalist is not subject to fasting and can carry on with their normal activities of hunting and married life. They acquire their knowledge through apprenticeship with another specialist and require a keen memory and perception.

The first sign that someone possesses the potential to be a shaman, to develop a relationship with the world of the yuxin, is failure to hunt. The shaman develops such a deep familiarity with the animal world (or with the yuxin of animals) that upon achieving dialogue with them, they cannot more killing them.

“And walking through the forest, the animal is talking to me,” he says. “When he sees a deer, he calls out, ‘Hey, brother-in-law,’ and then he stands still. When he sees a pig, he calls out, ‘Ah, my uncle,’ and he stays there. Then, in our words, he says ‘em txai huaí!’ (Hey, brother-in-law!), and he doesn’t eat it.” (Siã Osair Sales, Huni Kuin community, Brazilian Amazon).

During altered states of consciousness, the “bedu yuxin” travels, free from the body, in dreams, or when the person is in a trance, under the influence of rapé or ayahuasca. These journeys serve purposes beyond the healing of a specific illness. They are exploratory excursions. They seek to understand the world, its motivations, its causes, its effects, its connections.

Likewise, for the Huni Kuin, there are several types of illness: one physical (poison) and another spiritual (power). The illness caused by poison is the responsibility of the dauya (herbalist), while the illness caused by spiritual power (muka) has a mukaya (shaman) as its culprit. There is also a third type: illness caused by the “yuxin.”

Technology and the Huni Kuin

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Huni Kuin (or Kaxinawá) suffered violent attacks from rubber tappers, and their relations with white people were not peaceful until the mid-1950s. At that time, the Huni Kuin began to establish a barter economy with the non-Indigenous society of Brazil and Peru.

The Huni Kuin, skilled hunters, obtained hides, feathers, seeds, and other treasures gathered in the mysterious Amazon rainforest in exchange for manufactured tools that made their lives easier in basic tasks. Over time, they stopped using their arrows and began using rifles for hunting, thus becoming dependent on cartridges sold to them by the Western world.

The Huni Kuin thus lost their hunting autonomy, as new generations were not taught arrow-making or traditional hunting techniques. When cartridge prices rose, they began raising cattle and pigs, which drastically changed their way of life.

However, there are very diverse Huni Kuin communities, and in fact, most still hunt, even with firearms, which simply helps the hunters in their arduous and dangerous task.

Even in the smallest communities, they often have some basic amenities that make life easier without completely disrupting their way of life. For example, they usually have a communal refrigerator where they store meat that isn’t consumed immediately, as well as some vegetables.

They also usually have some tools that make farming easier, such as a chainsaw or a lawnmower. They generally have electricity from solar panels, although this doesn’t mean that every hut has light; rather, the electricity is used for communal purposes.

Typically, a gasoline-powered generator provides electricity and internet access to the entire community for one hour a day. This varies greatly from one community to another.

Some communities have electricity all day long, private cell phones, and some Huni Kuin have social media networks where they share their culture and showcase their villages. Some communities offer lodging to tourists in exchange for large sums of money, while other Huni Kuin communities remain more isolated and don’t need to participate in the formal economy through currency, relying instead on bartering.

The use of social media has, above all, facilitated their visibility across the globe, making their songs and prayers accessible to everyone.

A couple of decades ago, three young Huni Kuin leaders arrived in Rio de Janeiro with the idea of holding ceremonies outside their homeland for the first time. Today, many leaders travel to all five continents to offer rituals, giving them a thorough understanding of Western life, with its technologies and modern conveniences.

Huni Kuin

Huni Kuin

Huni Kuin

Huni Kuin